| Oral History Mainpage Oral Traditions: What They Are and Why They Are Important Bringing Oral History to the Classroom References Back to Ms. McKeen's Homepage |

|

| “Writing,

indeed any form of visual transcription of oral linguistic elements,

had important consequences for the accumulation, development and nature

of human knowledge.” -Jack Goody1

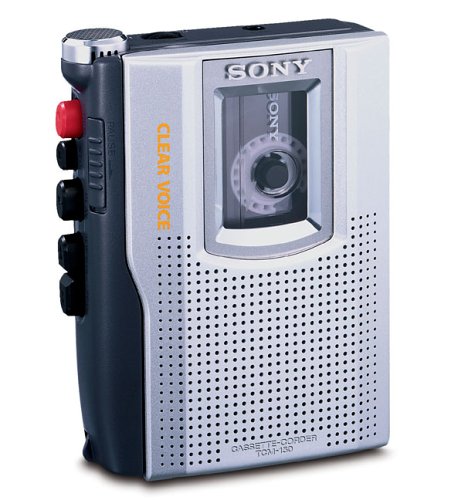

We are constantly discovering more sources of oral history, and this increase in sources has sparked debate over how to best record and disseminate this newfound knowledge.7 When it comes to finding an authentic way to document oral histories and traditions, there are many routes to take, and also many pitfalls to avoid. Historians and others who record this information must try to capture it in its truest form, and this is not always easy to do. This is especially true when the oral tradition is from a culture with a different language than that of the recorder, as some of the nuances of the oral tradition will necessarily be lost in translation. The recording process has been greatly improved since the invention of taperecorders, and then videocameras. These devices allow us to capture oral histories and traditions with much greater exactitude. Before these were available, the only means of recording information was to transcribe it which decontextualized the oral tradition and was also not always as accurate or authentic.1 There are many things to be cognizant of when documenting oral traditions, not the least of which is that “A narrative in print may be read centuries later, but it still was produced under specific social and economic conditions by authors whose attitudes to a perceived potential audience would have affected the way they presented their material. The social contexts of oral histories include the additional condition that their tellers must intersect with a palpable audience at a particular moment in time and space. What they choose to say is affected by these conditions, which also mean that they can get immediate feedback.”2 This quote, from Elizabeth Tonkin, perfectly points out what may well be the biggest problem we face when trying to maintain the authenticity of an oral tradition. When we record an oral tradition, we are directly creating an altered environment for the one who is sharing their knowledge. The recorder becomes the audience, and so influences the performance as the performer tries to adapt their telling to the percieved needs, attitudes, beliefs and purposes of the recorder. Recording oral histories is difficult because of the "very nature of the work." Because oral history is essentially the collecting of human narratives, we must remember that the human part of the work is always in a state of flux and so our documentation and dissemination techniques we use need to be flexible as well, and change with a changing society.7 Collecting the information is a daunting task. Not only this, but there is also the issue of deciding whose stories, and what knowledge, gets recorded. To try and meet both of these needs, there are some organizations that set-up places where people can go to get resources or have teh chance to record their own oral history and traditions. One such place is the San Francisco Center for Digital Storytelling. CDS also conducts workshops in order to educate people about the importance of oral traditions and histories. Sara Armstrong, an unofficial spokesperson for CDS speaks with many educational groups about the importance of digital storytelling and the collection of oral histories, and encourages teachers to find ways to bring this into their classrooms.4 For more information about this, please visit the Bringing Oral History to the Classroom page. Once the information is gathered, it must be made available to be of value. There are also organizations devoted to compiling and making available this recorded knowledge. One website where this information is made available is Oral History Online. This site contains over 2,000 oral history collections in English, with 129,000 pages of text, interviews of 4,300 individuals, 1,400 audio and video files, and 10,000 bibliographic records. In order to have access to this information, you must have a subscription. Lists of the information available is available without a subscription.6 |